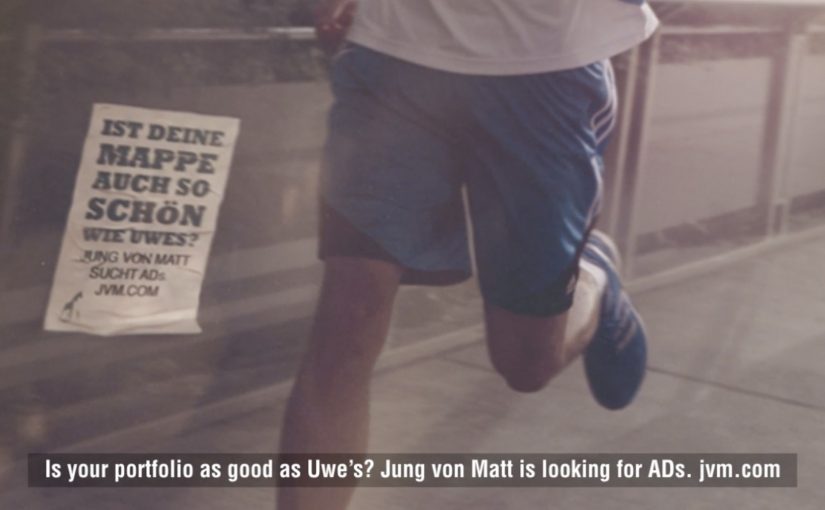

Jung von Matt is looking for talent again, this time art directors. Staying true to its creative reputation, the agency devised a cheeky way of recruiting from the same places competitors recruit from.

This time the “Trojan horses” were 15 well-known photographers whose work is regularly shown to top creative agencies in Germany. Jung von Matt’s job message was integrated into the photographers’ portfolios. An inscription on a bus. A graffiti on a wall. A stitchery on a pullover. The job ad appears inside the work, right where art directors and creatives are already paying attention.

Recruitment as a stealth placement inside creative culture

The mechanism is elegant. Instead of pushing job ads outward, the agency inserts them into a trusted distribution channel. Photographers’ portfolios are already a legitimate reason to visit creative departments. By embedding the hiring message into those images, the job ad arrives with credibility and surprise built in.

In agency recruitment, the most effective messages often travel through peer-to-peer channels where creative people already look for inspiration.

Why it lands

It respects the audience. Art directors do not want HR language. They want ideas. The recruitment message shows up as an idea. The “spot it” moment also creates a small status game. If you notice it, you feel like an insider, which is exactly the emotion you want associated with joining a top creative shop.

Extractable takeaway: If you recruit creative talent, do not only describe the culture. Deliver the culture as a recruiting experience. The medium should prove the message.

What Jung von Matt is really doing here

Beyond hiring, this is reputation maintenance. The campaign reinforces the belief that the agency thinks differently, even about recruitment. It also targets a very specific context. The moment when competitors are reviewing portfolios and looking for talent. That is when the message is most likely to be acted on.

What to steal

- Place your message in a trusted channel. Borrow the legitimacy of a format your audience already values.

- Integrate, do not interrupt. Embedding the ad inside the creative work makes it feel like discovery, not spam.

- Make the message audience-native. Speak in the language of the craft, not corporate templates.

- Target the decision moment. Put the offer where hiring intent already exists.

- Keep it simple. One clear role, one clear next step, no clutter.

A few fast answers before you act

What is the “Trojan Art Director” idea in one sentence?

It is a recruitment tactic where Jung von Matt embeds job messages inside photographers’ portfolio images that are regularly shown to top agencies, reaching art directors in-context.

Why are photographers’ portfolios a powerful distribution channel?

Because they are already viewed by creative departments and talent decision-makers. The audience is qualified and attention is high.

What makes this feel credible rather than gimmicky?

The message is integrated into real creative work and appears in a context where creativity is the currency. That makes the format match the audience expectation.

What is the main risk with stealth recruiting?

It can be perceived as hostile or disrespectful by peers if the tone is too aggressive. The balance is “cheeky” rather than “petty.”

How do you measure success for a recruitment stunt like this?

Qualified applications for the specific role, referral volume from the creative community, and whether employer brand perception improves among the target talent pool.