Two videos that did not just play, they proved the point

In digital marketing, video innovation rarely comes from “better footage”. It comes from changing how the viewer experiences the message. These two campaigns are clean examples of that approach.

In the last week or so I came across two campaigns that used video to innovatively deliver their message.

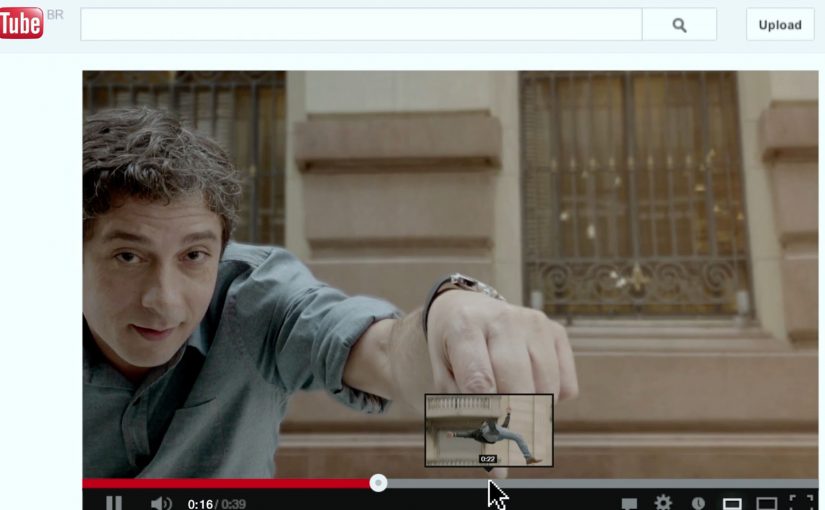

Volkswagen Hidden Frame – using the YouTube play bar as the story

The Volkswagen Side Assist feature helps drivers avoid accidents by showing other vehicles when they are in the side mirror’s blind spot.

To drive home the message, AlmapBBDO developed a film that used YouTube’s play bar to show the difference the VW Side Assist made in people’s lives.

No Means No – a player that interrupts denial

Amnesty Norway, in an attempt to change the Norwegian law on sexual assault and rape, developed a film that used a custom video player to pop up the key message.

The campaign was a success and the law was about to change as a direct consequence of the campaign.

Why interface-led video lands harder

Both ideas shift the viewer from passive watching to active noticing.

Volkswagen used a familiar interface to make a safety benefit visible in the moment. Amnesty used an interface interruption to force the key message to be seen, not skipped. In both cases, the “player” stopped being furniture and became the persuasion device.

In digital storytelling, interface design becomes a competitive advantage when it shapes what the viewer notices and cannot easily skip.

What these campaigns were really trying to achieve

The business intent was not “engagement” as a vanity metric. It was message delivery with minimal loss.

Volkswagen aimed to make an invisible feature feel tangible and memorable. Amnesty aimed to change perception and behavior at the cultural level, and the player design reinforced that urgency by refusing to be background noise.

What to steal from player-hacking storytelling

- Use the interface as evidence. When the message is hard to show, let the UI demonstrate it.

- Design for the skip reflex. If your message is often ignored, build an experience that makes ignoring harder.

- Keep viewer control intentional. Interactivity works when it serves comprehension, not novelty.

- Make the “point” happen inside the viewing moment. Do not rely on a voiceover claim when the experience can prove it.

A few fast answers before you act

What is an “interface-led” video campaign?

A campaign where the video player experience. The progress bar, overlays, or controls. Is part of the storytelling, not just the container.

How did Volkswagen Hidden Frame use YouTube differently?

It used YouTube’s play bar as a narrative device to demonstrate the value of Side Assist, making the benefit feel visible rather than described.

What did Amnesty Norway’s No Means No change about the player?

It used a custom video player that surfaced the key message via a popup, ensuring the point was encountered during playback.

Why do these ideas work better than a standard film in some cases?

Because they reduce message loss. The viewer is guided to notice the point through the viewing mechanics, not just the content.

What is the practical takeaway for brands?

If your message is often missed, redesign the viewing experience so the message is structurally harder to ignore and easier to understand.