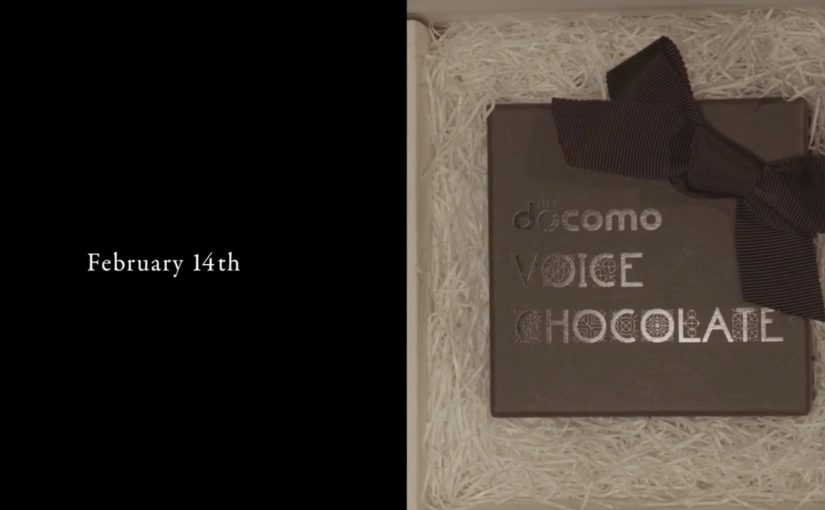

On Valentine’s Day, women in Japan record a voice message on their smartphone. That voice is transformed into a unique chocolate pattern, and a premium patisserie, Mont St. Clair, delivers the custom chocolates to the men they love. The recipient then uses a special app that recognises the AR markers in the chocolate, and the voice message plays back from the smartphone.

The campaign comes from Docomo (Japan’s largest mobile phone company) working with agency Hakuhodo. The business context is straightforward. Voice communication traffic falls sharply over the last 15 years, largely due to messaging apps. Docomo uses the ritual of Valentine gifting to make voice feel emotional and “worth using” again.

Why this works as mobile, packaging, and emotion in one system

This is not content about voice. It is voice turned into a physical artefact. The chocolate is both the gift and the interface. The phone becomes the capture tool. The app becomes the playback layer.

That combination matters because it closes the loop between human intent and digital capability. The message is not typed. It is spoken. It arrives as something tangible. Then it becomes audible again at the moment of receiving.

The pattern to steal

If you want to revive a behaviour that is losing ground, the structure here is repeatable:

- Find a culturally accepted moment where the behaviour already makes sense, in this case Valentine gifting.

- Convert the behaviour into a physical token people want to give and keep, not a disposable digital asset.

- Use an interaction layer (AR, scan, app) that reveals the emotional payload at the right moment, for the recipient.

A few fast answers before you act

What is “Voice Chocolate”?

A Valentine concept where a recorded voice message is transformed into a chocolate pattern, delivered as a gift, then played back via an app that recognises AR markers in the chocolate.

Who is behind it?

Docomo in partnership with Hakuhodo, with chocolates delivered with help from Mont St. Clair.

What problem is it addressing?

Falling voice communication usage driven by messaging apps, by making voice feel meaningful again through gifting.

What is the core experience design move?

Turn a voice message into a physical interface, then use a scan-to-reveal mechanic so the voice returns at the moment of receiving.