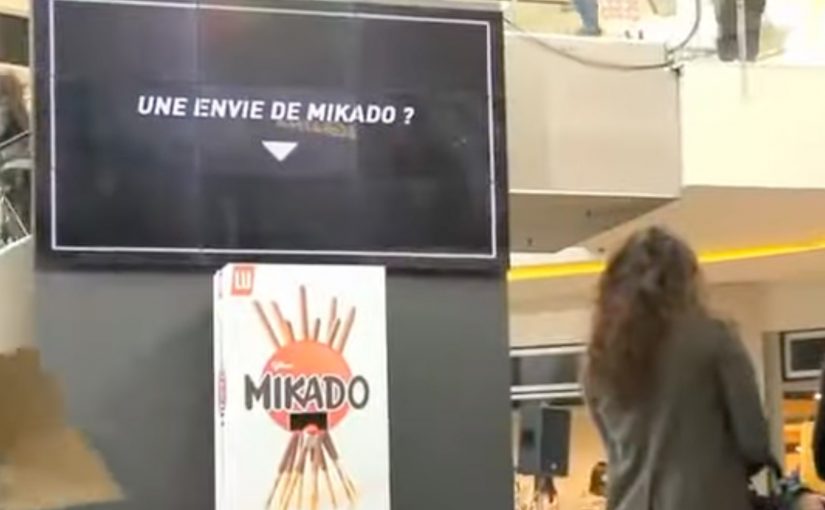

You are doing your shopping in a mall, and you spot a giant Mikado dispenser. Above it, a message scrolls: “Une envie de Mikado ? Vous ne devriez pas…”. A free box is right there. The temptation is immediate. People hesitate for half a second, then they reach for it anyway.

The moment the “victim” takes the Mikado, reality shifts. In a beat, they “fall” into an absurd, high-stakes scene. A nightmare wedding. A robbery. A knife-throwing scenario. Six variations. Each one staged to make a single point feel physical: Mikado is hard to resist, even when you are warned not to.

The idea in one line

Turn “irresistible” from a claim into a public dilemma. Then prove it by watching people choose temptation in front of everyone.

What Buzzman builds for Mikado

This is a deliberately simple setup with a brutal logic loop:

Step 1. Offer the product for free, but add a warning

The dispenser invites you, then immediately tells you not to do it. That contradiction creates tension and curiosity in the exact moment of decision.

Step 2. Make the consequence entertaining, not moralizing

When the actor takes the box, they “drop” into a surreal scenario. The audience in the mall watches the fall. Then they watch the scene unfold. The humor is the proof mechanic.

Step 3. Extend it into a digital series with repeat value

The campaign runs as a set of videos with multiple protagonists and outcomes. The variety matters because it turns one stunt into a format.

Step 4. Make the viewer complicit

At the end of the video experience, you can choose who becomes the next “victim.” That interactive twist is not a gimmick. It reinforces the theme: you are part of the temptation chain.

Why it works

It turns a brand truth into a behavioral test

The campaign does not explain why Mikado is irresistible. It sets up a moment where resisting is the story.

The warning is the creative fuel

“You shouldn’t” is what makes people want to do it. The copy creates the tension. The action resolves it.

The audience reaction is the distribution engine

People do not only watch the “victim.” They watch the crowd. The social proof is built into the scene itself.

The deeper point

If you want a product attribute to stick, stop describing it. Build a situation where people demonstrate it for you. Especially when the attribute is emotional (irresistible, addictive, impossible to ignore), the most persuasive proof is behavior under temptation.

A few fast answers before you act

What is the core mechanic?

A public dispenser offers free Mikado while warning you not to take it. When someone does, the stunt flips into a staged “consequence” scenario that proves irresistibility.

Why multiple scenarios?

Because a single stunt becomes a repeatable content format. Six outcomes keep it watchable and shareable.

What is the role of interactivity?

Viewers can choose the next “victim” at the end of the video experience, extending participation beyond the mall moment.

What is the transferable pattern?

Design a public “temptation test” where the desired product truth is demonstrated through behavior, not explained through messaging.

What is the biggest risk?

If the consequence feels mean-spirited or unsafe, the tension flips from funny to uncomfortable. The stunt has to stay playful.