If t-shirts can be digitised, then why can’t underwear. Durex Australia has unveiled “Fundawear”, billed as a first-of-its-kind wearable electronic underwear concept that allows touch to be transferred over the internet while maintaining comfort, sexiness and flexibility. The idea is simple. People in long-distance relationships can tease, tickle and tantalise even when apart.

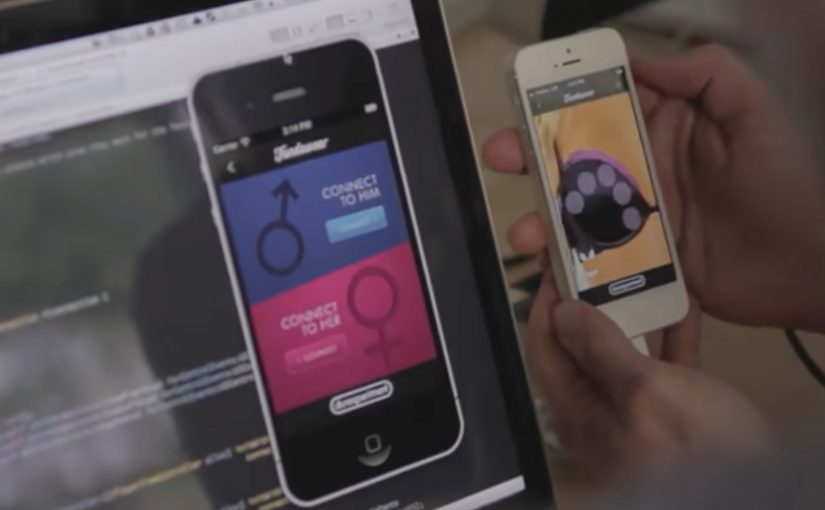

To replicate the nuances of touch, each garment houses touch technology that connects with a real-time server to communicate between touchscreen devices and the garments. Interaction happens through a smartphone interface, translating inputs into sensation on the connected wearable.

A prototype that behaves like a campaign

What makes this work stand out is the choice to launch as an experiment, not a finished product. Fundawear is framed as a prototype, which gives the brand permission to be bold, invite participation, and trigger debate, without pretending the tech is already mainstream.

It also shifts the job of the communications. Instead of persuading people that “remote touch” is a good idea, it makes people imagine use cases. That imagination is the marketing engine.

How the technology story earns attention

The campaign leans on a clear mechanism. Touch input on a phone maps to specific zones, then the garment responds, creating a feedback loop that feels like a live connection rather than a delayed message.

When wearable technology is explained this clearly, it stops sounding like science fiction and starts sounding like an interface decision. That is when people share it.

In consumer innovation marketing, the leap from novelty to adoption happens when a physical interface makes a digital promise feel immediate, controllable, and consent-led.

Distribution strategy: invite the internet to co-author the idea

Fundawear is described as still in the experimental stage, with no confirmed release date at the time. But Durex uses that uncertainty as a hook. If you provide a creative reply to “How would you use Fundawear with your partner?” at the Durex Facebook page, you might win a free prototype.

That is a smart move. It turns the public into contributors, and it generates word of mouth that carries the concept further than a conventional product launch could.

What to steal if you are launching an unfamiliar product concept

- Prototype publicly. Experiments can travel faster than “finished” products because people argue, imagine, and remix.

- Explain the mechanism in one breath. If the audience cannot repeat how it works, they will not share it.

- Design for participation. A prompt like “how would you use it?” converts curiosity into content.

- Keep the tone playful, not clinical. For intimate categories, playfulness lowers the barrier to talk about it.

A few fast answers before you act

What is Fundawear, in plain terms?

Fundawear is an experimental wearable concept from Durex Australia. It pairs smart underwear with a smartphone interface so a partner can send touch inputs over the internet in real time.

What kind of technology does it rely on?

It relies on wearable haptics, meaning small actuators in the garment respond to signals from an app. A server connection synchronises inputs between two partners’ devices and garments.

Why launch a prototype instead of waiting for a finished product?

Because a prototype creates permission to experiment, earn press, and test cultural appetite. It also turns uncertainty into participation, which can generate more talk than a polished launch.

What is the biggest brand risk with intimate wearable tech?

Trust. The concept has to feel safe and consent-led, and the communication has to avoid any hint of surveillance or misuse. If trust breaks, the idea becomes a cautionary tale.

What is the core marketing lesson from Fundawear?

When the product is unfamiliar, the first job is not persuasion. It is making the mechanism and the imagined benefit instantly understandable, so people do the distribution for you.